A year of the war. Did Russians change their mind?

I. Introduction

{{margin-small}}

February 24th marks the anniversary of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine or, as Putin called it, the “Special Military Operation” (”SMO”). The mere fact that the “SMO” has lasted for a year now shows that the invasion has not gone as initially planned, and the Russian leadership is unlikely to see a way out how to proceed with its military campaign in Ukraine.

Despite the widespread belief that Putin solely decided to invade Ukraine, our view is that Russian society had and may have its say on the relevant events. Unsurprisingly, Russia’s presidential administration regularly conducts its own polling, examining changes in public opinion.

Therefore, it is crucial to understand and comprehensively review how the attitudes of Russians towards the war have changed over the past year. In doing so, all complexities implied to such study by the current political regime in Russia and the lack of sufficient information have been considered.

In our 2022 Year Report the OMI team analysed the key trends in Russian society and provided the main factors determining support for the war, with authoritarian obedience being the key one. This time OMI has delved deeper into the online behavior of Russians so as divide Russian society in the relevant groups, each with its own distinct beliefs.

{{margin-small}}

This Report will:

- cover the general trends of the dynamics within Russian society in regards to the war in Ukraine based on the relevant web search data, online posts and social media comments and compare it to public sociological research data;

- provide a short summary of the unpublished focus groups to reveal what Russians themselves actually say about the war;

- analyse evident sources and conclude what the real segmentation of the Russian society, based on their war attitudes, might look like; and

- end up with a short summary covering changes (if any) in the way Russians think about the war as compared with February 2022.

{{margin-big}}

II. Online Data Findings and Polling

{{margin-small}}

Readiness to End the War

{{margin-small}}

The most pressing question regarding the war is when it will end. There are several factors that may lead to a resolution, including a decisive victory by one side or a willingness to reach a compromise by one of the countries involved.

While some argue that the decision lies solely with Russian President Vladimir Putin, public opinion among Russians is a potential significant factor that could impact his stance. The President of Russia needs to have the support of the people if he decides to withdraw forces or negotiate acceptable terms with Ukraine.

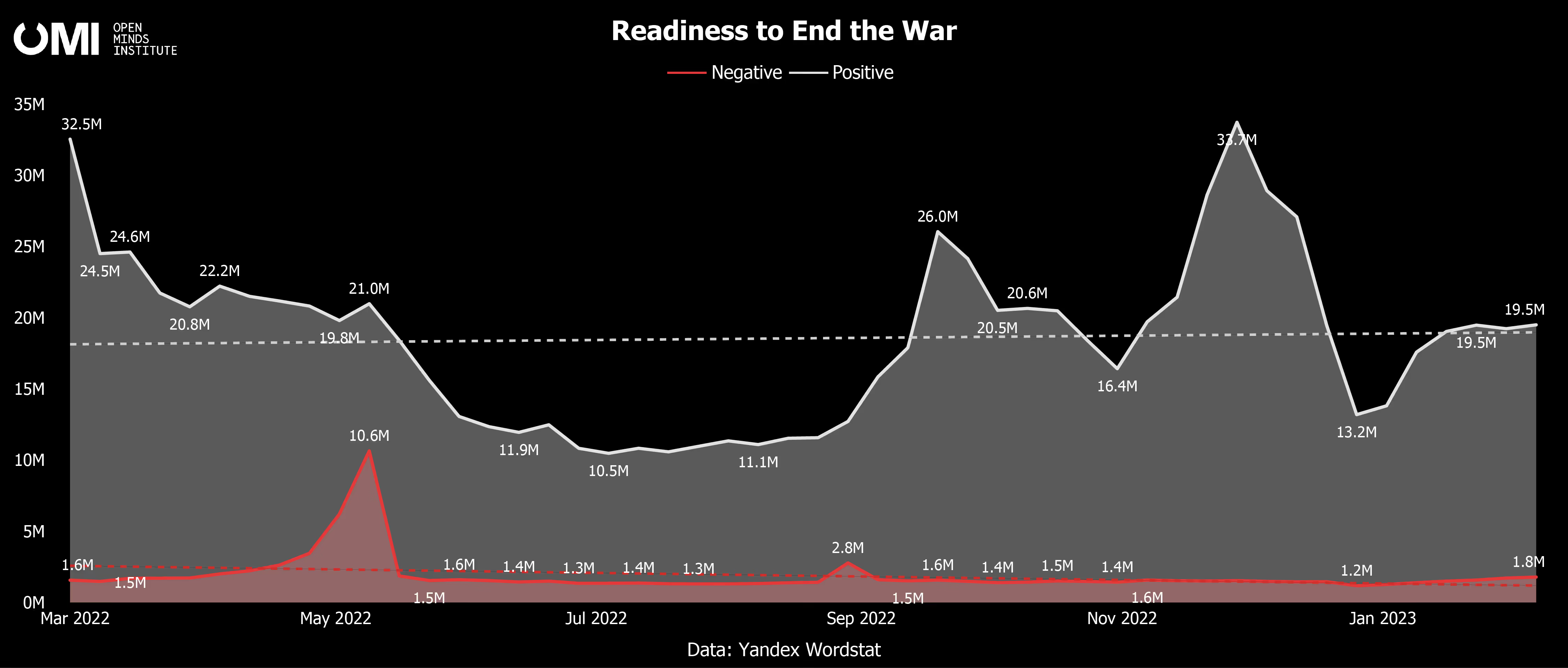

The chart below shows the dynamics of online searches that may indicate attitudes among Russians toward ending the war. The trend lines indicate that the negative attitude towards ending the war is relatively stable, except for a spike in such searches in May (e.g., "the war is inevitable," "until victory").

The positive attitude towards ending the war (e.g., “when will there be peace?,” “how to end the war”) varied throughout the year, with three main spikes in data - at the beginning of the war, in September when “partial“ mobilization in Russia was announced, and in November when the Ukrainian Armed Forces liberated the city of Kherson and missiles hit Polish soil.

There were fewer online searches indicating readiness to end the war during the summer, which may have been due to a decrease in overall interest in the war after the first months of invasion and before Ukraine's counteroffensive operations began. Overall, the trend for readiness to end the war over the year has been positive but not significantly so.

{{margin-small}}

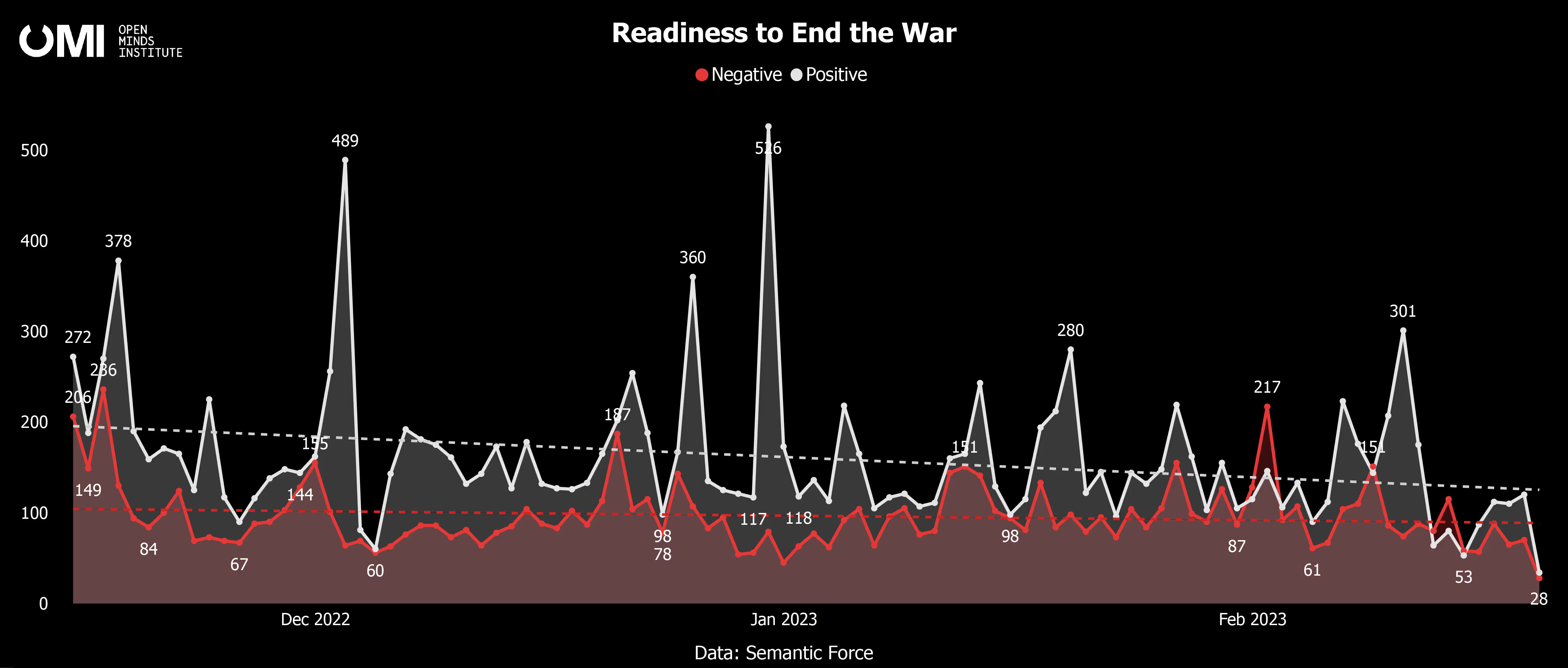

Now, turning to online discussions of Russians during the last three months. From November 15th to February 19th, both trends had been negative, indicating that Russians were likely to express less positive and negative attitudes towards the war.

The main events that could have triggered spikes in positive attitudes to end the war were the sanctions on Russian oil, New Year's Eve, and the explosions at Russia's Engels airbase. The spikes in negative attitudes towards ending the war occurred during the days of mass air attacks on Ukraine's infrastructure, the start of the China-Russia joint naval exercises, and an interview with Russia's foreign minister Lavrov.

{{margin-small}}

{{margin-big}}

Perception of the Impact of the War

{{margin-small}}

When discussing the impact of the war on Russia, it is important to distinguish between objective reality and the perception of the impact by Russian citizens. While the Russian government's propaganda has been effective in covering up the true economic impact of the war, due to conscription, it is likely that almost everyone in Russia is directly involved in the war or knows someone who is.

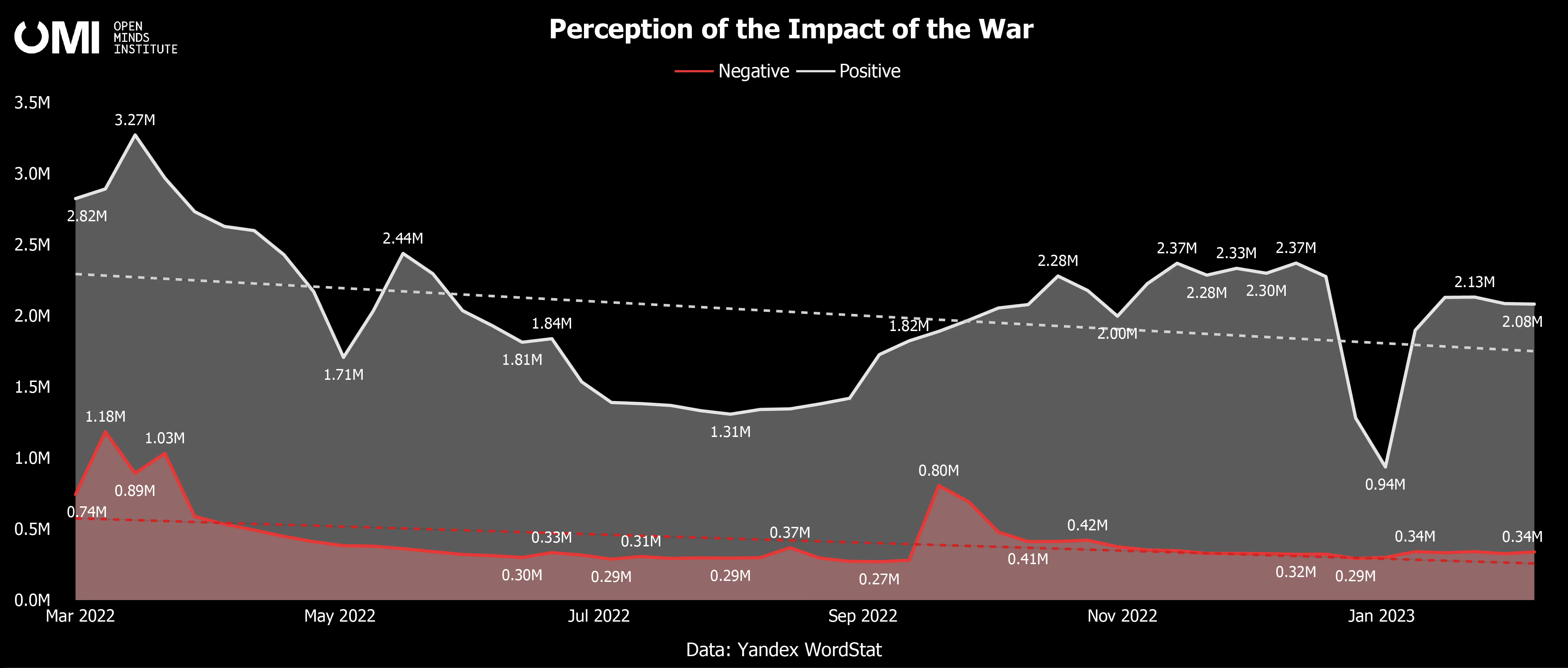

The chart below shows a similar pattern to the one observed for readiness to end the war. The number of searches related to the impact of the war was higher at the beginning of the invasion and during autumn, with a lull during the summer. Over the year, both negative (e.g., “companies are leaving,” “casualties of war”) and positive searches have shown negative dynamics, likely due to exhaustion with the war after a year of conflict.

In March, there was a spike in searches related to the negative impact of the war, likely due to the first sanctions applied to Russia, foreign companies leaving the Russian market, and the dramatic decline in the value of the Russian ruble. However, there was also a high number of searches indicating a positive impact of the war, such as "It has gotten better," "Our production growth," and "New Russian territories."

A spike in negative impact was observed around the time when “partial” mobilization was announced, and there was an abrupt drop in positive impact around the time of New Year celebrations.

{{margin-big}}

Sentiments about the Direction of the Country

{{margin-small}}

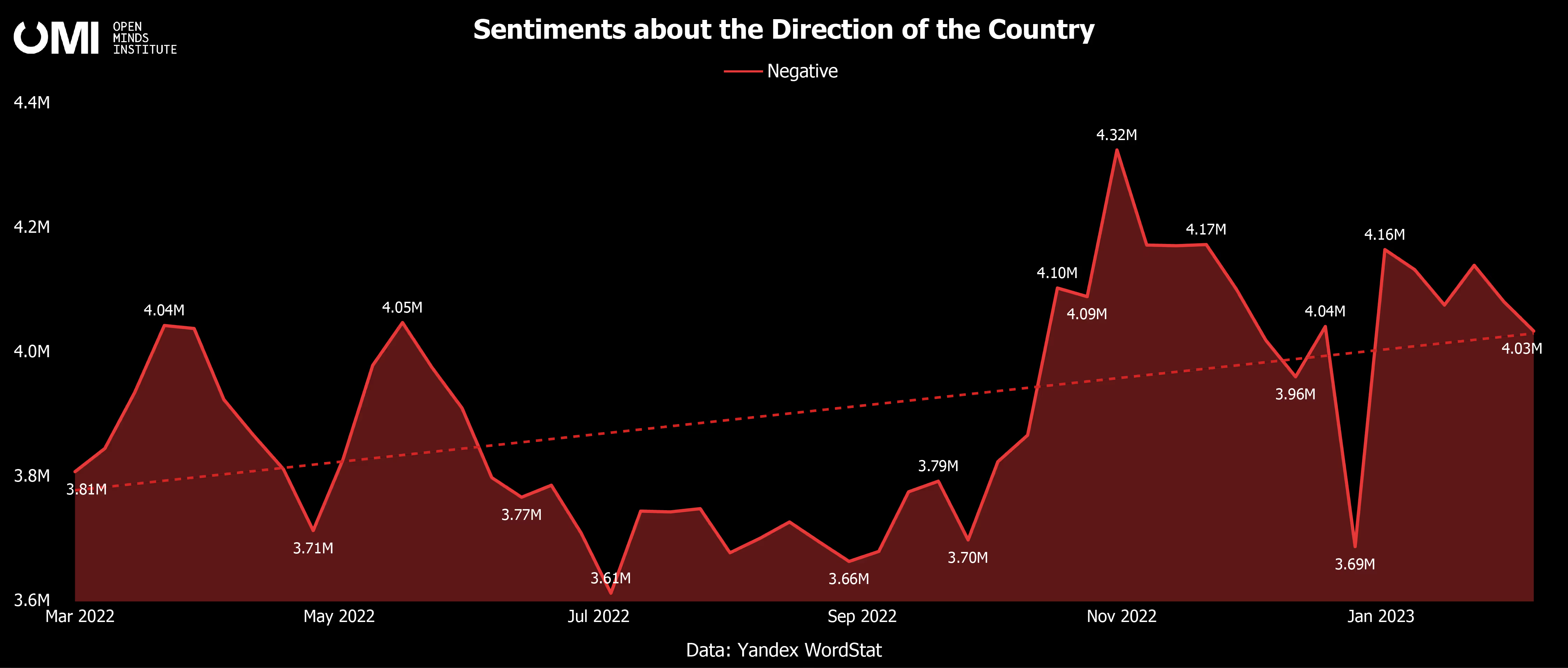

It seems that despite censorship, Russians are not hesitant to express their disappointment and negative sentiment towards the government and the direction of the country (e.g., “Russia in catastrophe,” “we are losing everything”), as seen through their online searches.

The pattern of lower numbers during summer can be attributed to previous explanations given for similar cases. Comparing the first months of the war to the spike in data after Ukraine's counteroffensive operations, it appears that Russians were more concerned about the country's direction when Russian forces started losing ground than when Russia started the aggression.

The highest spike in data occurred around October 31st, when Russia launched a mass air strike on Ukraine and the Russian-occupied Crimean naval base was attacked. This event led to increased searches expressing negative sentiment. Overall, the trend line suggests that throughout the year, Russians tend to reflect negatively on the direction of their country more.

{{margin-big}}

Willingness to fight

{{margin-small}}

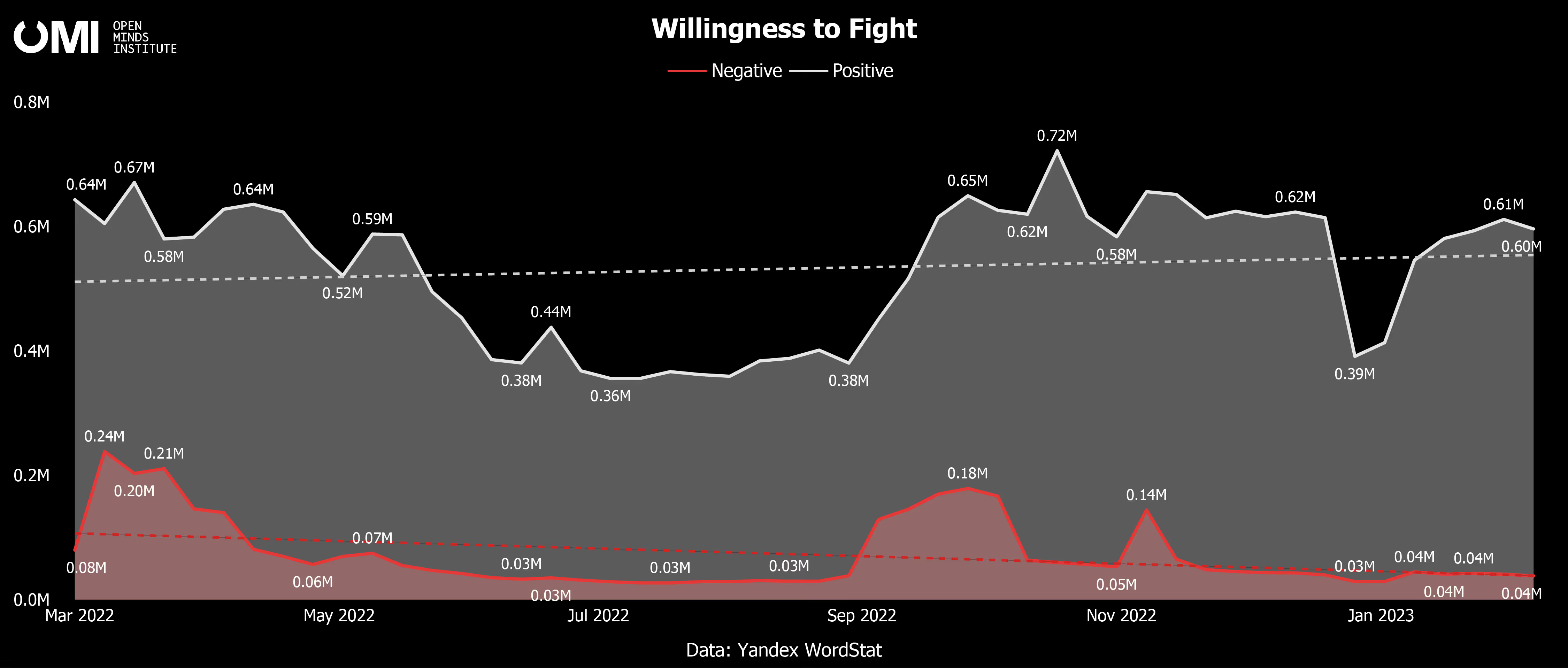

The announcement of “partial” mobilization in Russia marked a significant turning point in the way Russians perceived the war. This event had a discernible impact on various aspects related to the war.

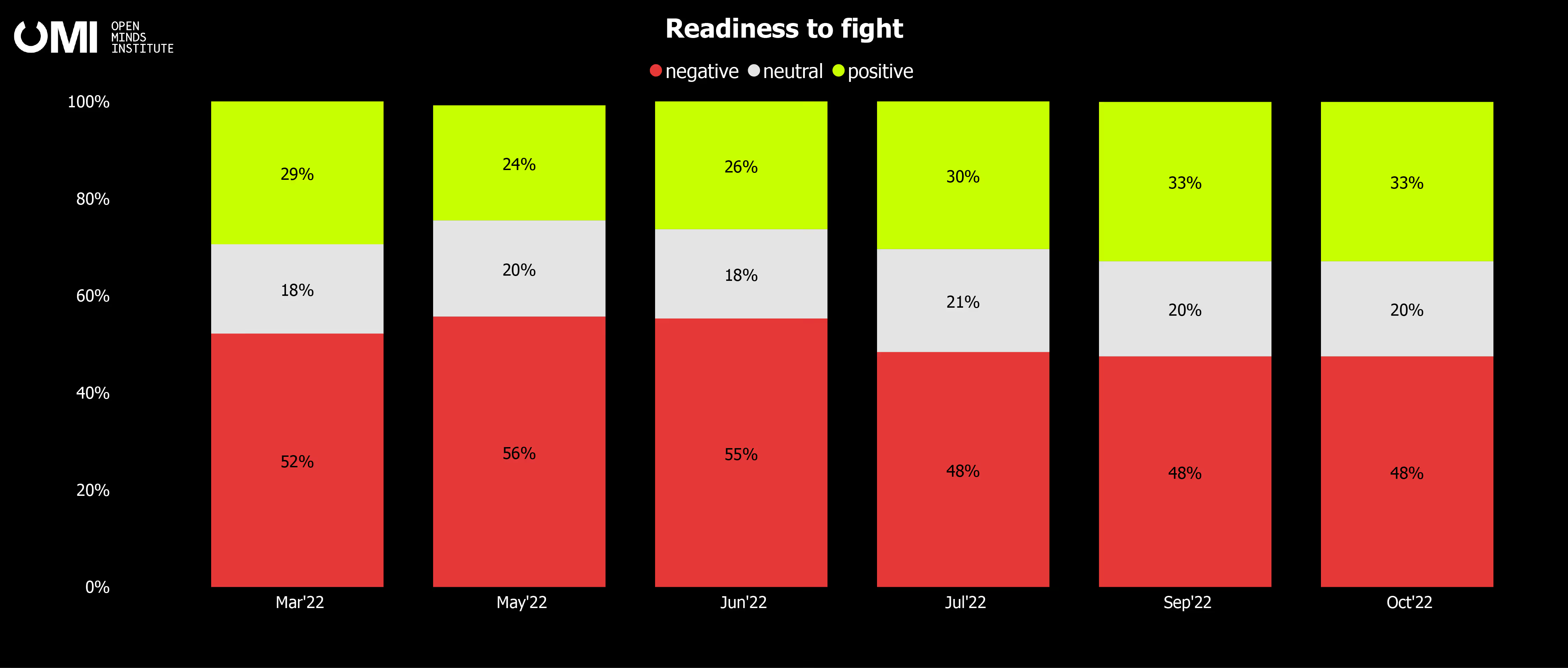

However, our online surveys revealed no significant differences in the readiness to fight among Russians in September and October, despite the conscription announcement. Based on the respondents' declared willingness to fight, we can conclude that there was an upward trend since July, with more people answering positively compared to the first three surveys.

Comparing these results with the data based on online searches, we confirm the overall trend of increased willingness to fight (e.g., “defend the motherland,” “we don't leave ours”) throughout the year.

However, there are some differences to note. Since the beginning of September and until the first days of October, we observed a spike in the numbers of negative attitudes towards hostilities. This increase in negativity may have been due to Ukraine's counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region and the announcement of conscription in Russia.

It is possible that although Russians continued to declare their willingness to fight in the war when asked, just like before these events, they were much more concerned in reality. This also suggests a mass exodus of men of conscription age from the country.

We also observed a spike in negative comments (e.g. “avoid conscription” and ”how to leave Russia”) on the matter in November when the Ukrainian forces launched another successful counteroffensive and reached Kherson city.

However, the effect of this event was relatively short-term compared to the spike seen in September. One reason explaining such difference is that the breakthrough of the Ukrainian forces was obvious for many in contrast to the one in September, and the Russians were accustomed to the fact that their army was not as invincible as they had previously thought. Therefore, the effect of the subsequent retreat did not last as long.

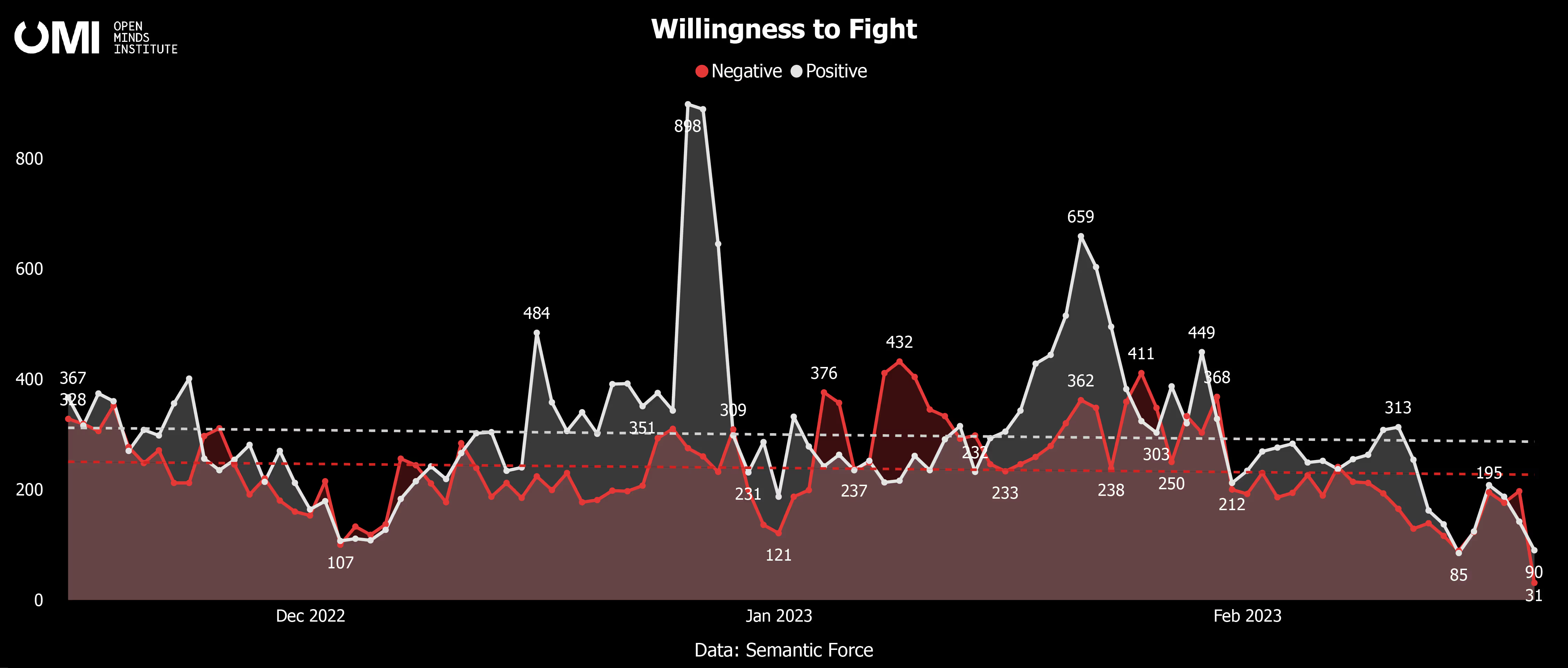

Looking at the last three months of the war, we observe that both negative and positive attitudes towards fighting remain relatively stable based on the trend lines of social media comments.

However, we also see abrupt spikes in data. On December 26-27, Russia claimed an attack by Ukrainian drones near the Russian Engels-2 airbase, and Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov announced new demands for peace talks which were not accepted. These events could have contributed to the spike in willingness to fight, but the numbers dropped back to their previous levels within two days.

{{margin-big}}

Trust in Government

{{margin-small}}

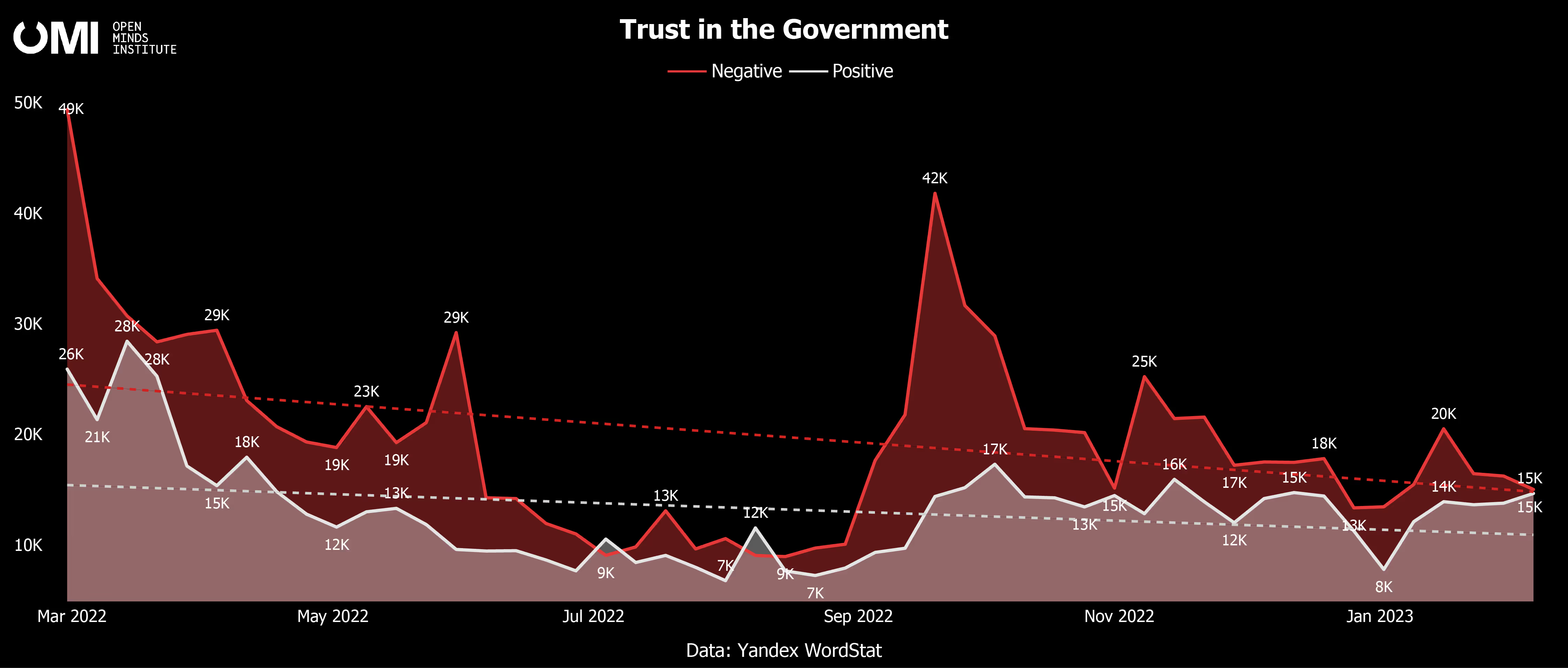

We began this report by stating that many people believe that the key to resolving the war in Ukraine lies in the hands of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Until one side achieves absolute dominance on the battlefield, Putin and his government may be put in a situation where the retreat of Russian forces becomes inevitable. One factor that can pressure such a decision is a rapid change in support for the war and the government by the Russian population.

However, after a year of the war, we do not see such predispositions among Russians. As described earlier, there has been some growth in positive attitudes toward ending the war, but it has not been significant enough.

Looking at trust in the government based on online searches, we see a decline in both positive (e.g., “Putin well done,” “government does right”) and negative attitudes (e.g., “against the government,” “Putin lost”). Moreover, the downward trend of negative comments is more rapid than the positive one.

It is worth noting that the announcement of the “partial” conscription undermined trust in the government the most since the beginning of the war. The Russian withdrawal from Kherson also left a mark as a spike in distrust of the government. Nevertheless, it is clear that as the year progressed, there were fewer triggers to cause a significant spike in negative attitudes.

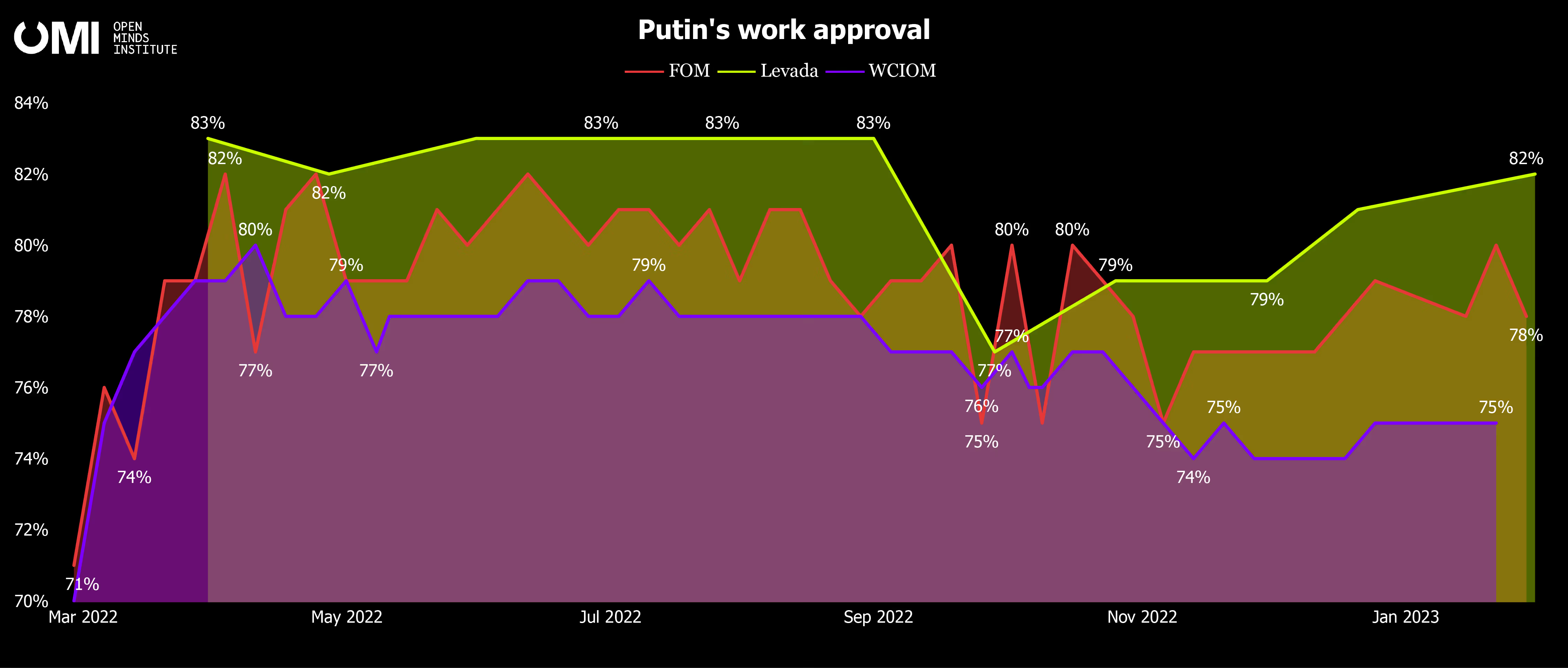

To reinforce our findings, we can examine the percentage of Russians who responded positively to the question of whether they approve of Vladimir Putin's work.

We can compare the results of three Russian sociological institutions (FOM, Levada, WCIOM), which conducted similar surveys during the year of the war. Based on such data, the Russian invasion of Ukraine only increased the number of Putin's supporters. Before the invasion, between 61% and 69% of people were satisfied with Putin's work. After the first month of the war, these numbers ranged between 75% and 82% up until the one-year anniversary.

{{margin-big}}

Summary

{{margin-small}}

The analysis of various sources and indicators shows that Russian public opinion on war-related topics is nuanced and complex. While some indications suggest a growing number of Russians are tired of the war and would like to see it end, there is no clear evidence of a widespread or significant shift in public sentiment.

Furthermore, some segments of the population have lost trust in the government's handling of the war, particularly after the announcement of “partial” mobilization. However, the erosion of trust appears to have been temporary, and overall trust in the government remains relatively stable.

Regarding attitudes towards fighting in the war, there have been fluctuations over time, often linked to specific events, such as military offensives or government announcements. Nevertheless, there has not been a gradual decrease in the willingness to fight.

{{margin-big}}

III. In their own words

{{margin-small}}

The unpublished focus groups conducted in January 2023 generally repeat insights reported in our 2022 Year Report: most perceive war as the new norm but try to distance themselves from the front news and feel like nothing depends on them. New trends, however, emerged.

More and more often, respondents mention the “SMO” is not going according to the plan, primarily because it's taking so long. Yet, they're ready for a prolonged war. They also doubt the rationale behind the "SMO" which was allegedly to protect people in Donbas and ambiguously state that the fundamental reason for starting the military operation is "big politics.”

Russians also don't trust the official sources on losses in the war anymore, as the government releases no precise information while increasing mobilization efforts. There’s also an increasing fear of the draft, especially since some of the previously mobilized Russians are returning home for rotations and telling the horrors of the reality in Ukraine.

As the tradition goes, after naming all the “SMO” related problems and a long list of issues within the country, like corruption, police violence, and problems with the healthcare and education system, respondents still answer that Russia is moving in the right direction under Putin's rule.

{{margin-big}}

IV. Society layout

{{margin-small}}

In the findings above, we described the trends in Russian society as a whole, but what is the underlying structure of it? There are multiple approaches to clustering Russian society into segments. They all vary in the variables used to make these distinctions and the resulting number and types of clusters. We will examine few of them and finalize with a conclusion of the Russian society layout.

{{margin-small}}

Anonymous studies

{{margin-small}}

At the dawn of the full-scale invasion, anonymous authors conducted a survey, revealing three main clusters, with two being further divided into two subgroups.

Pro-war audience

The Passionate group (23%) displays a group of primarily older men with fervent enthusiasm and optimism, harboring a combative stance and advocating for Russia to persevere in the war until the end. Individuals belonging to the Obedient Patient group (33%) possess a sense of hope, despite not anticipating any meaningful improvement in their personal circumstances and identify with a powerful entity that places trust in its leadership's decisions.

Anti-war audience

Individuals belonging to the group Russians Against War (14%) harbor pessimistic sentiments, holding a conviction that the country's situation will deteriorate.

They strongly oppose the war and attribute its responsibility to Russia, fervently hoping for its cessation. Despite their discontent, they maintain a sense of attachment and belonging to their country. This group comprises a larger proportion of young individuals and fewer elderly individuals.

Individuals belonging to the group of Internal Immigrants (7%) are horrified by the ongoing conflict and vehemently oppose the war, holding Russia responsible for instigating it. They feel profoundly estranged and unhappy, unwilling to engage in communication with their fellow countrymen. This group is marginalized and does not identify with Russia as their country.

Other groups

Individuals belonging to the Pro-USSR but against the government group (10%) express skepticism regarding the rationality of the war and anticipate a decline in their standard of living. They harbor concerns about the state of affairs in Russia and attribute it to the government's erroneous and unproductive efforts to revive the Soviet Union.

The group who exhibit Little Interest in Politics (12%) feel trapped and uncertain but hold the view that politics and war do not pertain to them. They lead private lives, primarily residing in small towns and rural areas. Although they do not actively endorse the war, they strive to remain uninvolved in the conflict.

{{margin-small}}

Experts’ thoughts

{{margin-small}}

Another attempt to provide a real picture of Russian society’s segments was performed by a sociologist A. Titkov. He utilized the survey results of Russian Field to classify Russians into distinct groups based on their attitude towards the war against Ukraine.

As of mid-July 2022, his breakdown suggestion was as follows:

~25% – War Enthusiasts: "hooray, let's go!"

~25% – Authority Supporters: "must mean must"

~20% – Conformity Supporters "well, I root for ours, but somehow I don't like it all"

~20% – Anti-War Advocates: "no!".

~10% – Uncertain/Not Involved

This categorization method, though providing some valuable information, may be somewhat imprecise and speculative. It also does not provide any further insight into the characteristics of individuals within each group.

Former Putin speechwriter, a political scientist Abbas Gallyamov, who has been labelled a 'foreign agent' by the Russian government for his criticism of the regime, has also published a bit more complex analysis of the society layout.

He analysed data from several dozen surveys conducted by the Levada Center and ZIRCON, which are well-regarded pollsters in Russia (despite the difficulties that pollsters experience in the current climate). He interpreted them in this manner:

- About a third of citizens are in varying degrees of opposition to Putin:

- Consistent opponents of the regime and the war (about 8%);

- "Opposition periphery": democratically minded citizens who are unhappy with the war but afraid to speak out openly against it (about 15%);

- "Semi-opposition": they are not ideological enemies of the regime but are dissatisfied with the quality of governance and life (about 10%). - Loyal to Putin and generally support his actions (around 40%):

- Aggressive anti-liberals, a steady core of support for Putin and the military operation (about 10%);

- "Power periphery" - people who generally agree with Kremlin rhetoric but are unhappy with repression (around 20%): they have a mature demand for change;

- "Semi-opposition": they are not ideological enemies of the regime but are dissatisfied with the quality of governance and life (about 10%).

- "Semi-loyalists" - they support those with power and could swing towards the opposition (10%) if certain developments occur. - Another quarter of the population is apolitical and uncertain in their sympathies – under the influence of aggressive propaganda they supported the invasion of Ukraine. But their interest in the war is fading fast, and their quality of life is less and less pleasing.

Gallyamov suggests that at the outbreak of the full-scale war, supporters and opponents of the regime were in rough equilibrium, with neither having a clear advantage.

{{margin-small}}

OMI findings

{{margin-small}}

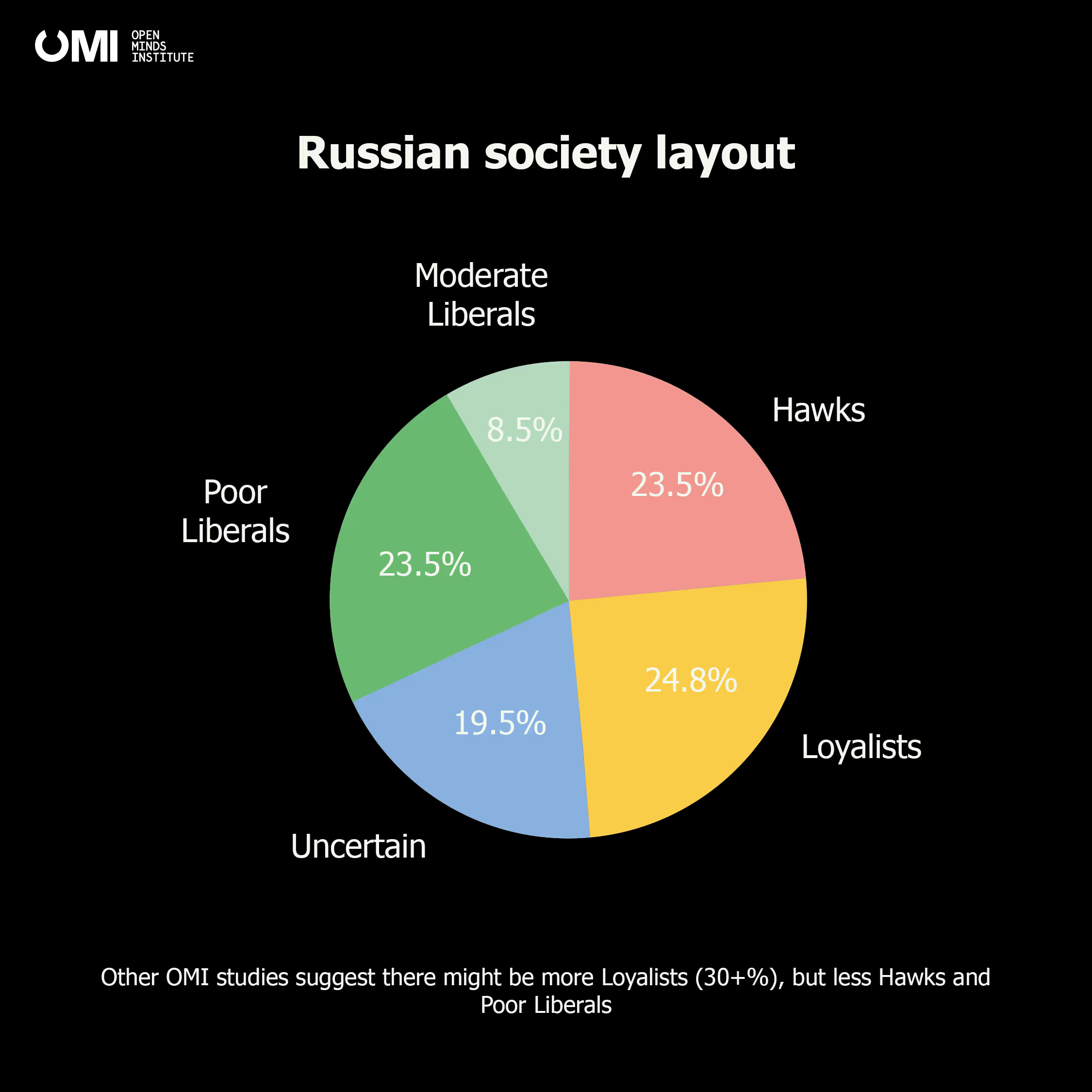

By the end of 2022 OMI team has conducted its own study to identify the segments of the Russian society. Besides standard socio-demographical and war attitudes variables, we have also included various personality traits and socio-psychological features: i.e., authoritarian obedience, personal self-efficaccy, levels of burnout and stress. See Annex 1 for the complete list.

The final result consisted of the following:

- Hawks (23.5%) believe that Russia is moving in the right direction, support the war against Ukraine, identify themselves with Russia and Russians, believe in themselves and their group, have low stress levels, and are psychologically well.

- Loyalists (24.8%) believe that Russia is moving in the right direction, support the war against Ukraine, identify themselves with Russia and the Russians, and believe in their strength and their group, but to a much lesser extent than the hawks. The stress level is average for the sample, but they are high in authoritarian obedience: believe that the government is always right.

- According to Poor Liberals (23.5%), Russia is moving in a catastrophic direction. They oppose the war, do not identify themselves with Russia and Russians. They do not believe in their own strength and in the strength of the group. The level of stress is the highest in the sample, and the indicators of psychological, emotional, and even social well-being are the lowest.

- Uncertain (19.5%) have average rates of support for the war in the sample, they are not sure if Russia is moving in the right or wrong direction, but they have the same level of psychological suffering as those of Poor Liberals.

- Moderate Liberals (8.5%) have views similar to Poor Liberals but not so pronounced. They’re also more prosperous and older than the latter.

Based on our research, we found that anti-war Russians tend to feel unhappy, experiencing high levels of stress and emotional burnout, and do not believe they have any influence on the situation in the country. They tend to be younger and more educated than those who support the war. Conversely, supporters of the war tend to be psychologically resilient, feeling confident and optimistic about the future.

The Hawks and Poor Liberals demonstrated the highest level of engagement in the war news, while the Uncertain and Moderate Liberals display the lowest levels. The pro-war groups have a tendency to consume news from federal television channels. Instead, the Poor Liberals and, to some extent, the Moderate Liberals rely primarily on information available on YouTube.

Individuals in the uncertain group appear to derive information from various sources, with liberal anti-war media holding a slight advantage.

It all suggests that some members of this group may harbor anti-war sentiments but remain uncertain or reluctant to express opposition, even in the context of an anonymous questionnaire.

{{margin-small}}

Summary

{{margin-small}}

All the clustering methods that we have examined, both through research and experts evaluation, position the clusters on a continuum, with passionate supporters of the ongoing war on one end and equally passionate opponents on the other.

Typically, the more passive pro-war individuals, who are inclined towards war by virtue of their trust in the authorities and conformity, as well as moderate supporters of peace, are placed between them. This trend is observable, irrespective of whether the basis for clustering is solely attitudes toward war or if demographic, sociological, and psychological criteria are included.

As stated by Gallyamov, convinced supporters and opponents of the war seem to be in rough equilibrium, with neither having a clear advantage.

The war and repression have given the regime a greater advantage, but public opinion is still ambivalent overall. The presence of 10-25% of ideological supporters of the war implies that a shift in state policy is unlikely to trigger a significant protest against ending the war.

Active supporters of the war with Ukraine may feel increasingly frustrated due to the failures of the Russian army at the front. This frustration is less intense than that of convinced opponents of the war but is still significant. The militarized Russians' discontent will likely grow as the conflict drags on.

{{margin-big}}

V. Conclusion

{{margin-small}}

The attitudes of Russians towards the war are crucial to monitor because they could signal significant changes in the political landscape, as has been seen in history.

While propaganda narratives in Russia may be influential, and there have been no significant shifts in Russians’ minds for the past year, there are indications that Russians tend to express negative attitudes towards specific issues, especially if fueled by evident military defeats and political failures.

Confidence in the political and military leadership is being gradually replaced with a lack of interest in ongoing war, or apparent signs of doubts Russians express while hearing official data or comments on losses on the battlefield or decisions adopted by their government to address the current economic and other issues.

The trend (where Russians have increasingly negative attitudes) may grow even more robust with potential future military losses and an aggravated economic situation.

The resulting unpredictability could have far-reaching consequences if combined with a lack of trust towards the government. In this regard, it is apparent that Russians have their word to say in the final resolution of the war, together with a complex interplay of military, political, and social factors within and outside Russia and Ukraine. Therefore, it is essential to keep a close eye on the Russian public's perception of the ongoing war, the same as Russian authorities regularly do.

{{margin-big}}

Annex 1. Variables used for clustering

{{margin-small}}

- Age

- Sex

- Education

- Financial changes during the last half a year

- Financial state

{{margin-small}}

Personality and social-psychological variables:

{{margin-small}}

Positive affect — the number and intensity of positive emotions experienced by a person in the last two weeks.

Negative affect — the number and intensity of negative emotions experienced by a person in the last two weeks.

Emotional well-being — the ability to produce positive emotions, moods, thoughts, and feelings and adapt when confronted with adversity and stressful situations.

Social well-being — the ability to communicate with others and build meaningful relationships where one can freely be him or herself.

Psychological well-being — good mental health, a sense of happiness, and satisfaction with life as a whole.

General well-being — the sum of emotional, social, and psychological well-being scales.

Russian identity — a sense of belonging to the Russians and a positive attitude towards the Russians.

Collective narcissism — the tendency to exaggerate the positive image and importance of a group (here — Russian nation) to which one belongs.

Perceived stress – Overvoltage — feeling of tension, anxiety, and worrying.

Failure to deal with stress — difficulties in coping with personal problems and difficult life circumstances

General stress — a state of mental or emotional strain or tension resulting from adverse or demanding circumstances.

Personal self-efficacy — an individual's belief in their capacity to act in the ways necessary to reach specific goals in politics.

Collective self-efficacy — an individual's belief in their capacity to act in the ways necessary to reach specific political goals together with other people.

Blind patriotism — the idea that one's state must be supported even if it creates injustice.

Constructive patriotism — the idea that one's state should be criticized and withheld support if it acts incorrectly and unfairly.

Authoritarian obedience — belief in the correctness and wisdom of the authorities, rejection of the opposition with an alternative assessment of what is happening.

Conservatism — belief in the moral superiority of previous generations and the need to honor traditions.

Authoritarian aggression — belief in the need for a strong and decisive leader who should direct society on the true path.

Burnout — feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one's life, feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's life and the world as a whole.

.svg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-01-2.avif)

-01.avif)

-01%25202-p-500.avif)