Digital Gulag, Bombings By The Russian Jets: What Disgust, Scare, And Enrage Russians?

Introduction

{{margin-small}}

In the new OMI study, we analyzed what anti-war and anti-regime messages may change Russians’ attitudes toward the invasion and country officials. As appeared, these messages don’t immediately change the way Russians perceive their country’s direction or peace negotiations. However, some make them feel really worried, disgusted and angry,

{{margin-big}}

Executive Summary

{{margin-small}}

- Reading messages about war generates negative emotions. Especially impactful are those about the future digital concentration camp and the threat of accidental Russian bombing of Russian cities (like it was in Belgorod). Such narratives can undermine Russians’ sense of security and create a vicious image of the totalitarian government.

- The use of the narratives can highlight the authorities’ role in the negative consequences of the war, such as the economic uncertainty or increasing dependency on China and decrease support for the war among Russians. Additionally, appealing to emotions like fear and disgust, often elicited by war narratives, may help mobilize public opposition.

{{margin-big}}

Methodology

{{margin-small}}

We asked a sample of Russians to read different anti-war or anti-government narratives. Afterwards, we inquired about their emotional response and whether they found the narratives persuasive.

{{margin-small}}

SAMPLE

Respondents were recruited online.

The sample was stratified by sex and age (equal age and sex groups 18-30, 31-44, 45-60 years). The data was cleaned, and the analysis excluded people who did not answer all the questions. The final sample consisted of 1051 respondents, 508 men, and 543 women. The mean age of the respondents is 37.14, the standard deviation is 11.46.

{{margin-small}}

STUDY DESIGN

{{margin-small}}

An intergroup design was chosen for the study.

The subjects answered a series of socio-demographic questions, and then read one of the texts that was offered to them randomly:

- “The Chinese yoke”: We were sovereign until we stuck our necks in the Chinese noose. Our relationship with China, our main geopolitical ally, is far from equal, making us vulnerable to exploitation. It's crucial to seek peace with the West before Chinese ambitions threaten our Siberian and Far East territories.

- “Digital concentration camp”: Without a QR code of loyalty and trustworthiness to Putin, you can't go into a store. Russia is becoming a digital concentration camp, with Chinese surveillance technology monitoring citizens and controlling their lives. As modern technologies combine with Putin's admiration for Stalin, the country risks repeating a dark past of oppression and suffering under an unyielding regime.

- “Regain stability”: Putin promised stability, security, and confidence in the future, but he failed us after starting the “Special Military Operation.” There’s no economic security, you’re required to fight in the war. The only way to regain stability is to start peace negotiations and end the war.

- “Russian bombs threat”: The tragedy in Belgorod, where a Russian plane accidentally bombed its own city, reflects the poor quality of Russia's remaining military equipment, ammunition, and personnel qualifications. As the war continues, Russia will likely experience more military accidents, making it crucial for the country to end the conflict and focus on modernizing its armed forces to ensure its own safety, rather than posing a threat to Ukraine and the West.

- “Russia Without Friends”: Russia has lost its traditional post-Soviet allies, leaving it with few partners to rely on in the face of a powerful alliance like NATO. As the country fails to gain new allies and loses its sphere of influence to Turkey and China, it becomes evident that the war must end, since victory in isolation is unattainable and the true strength of Russian armed forces has been overestimated.

- The control group read a neutral, non-political text about the psychological traits associated with procrastination.

The answers of the control group were perceived as a baseline, and the indicators of other, experimental, groups were compared with them. Then the subjects answered questions about the country’s direction, the relationship between the problems of people in Russia and the “special military operation” in Ukraine, and the readiness for the sake of peace to stop the war and return certain territories to Ukraine up to the Donbas and Crimea (a series of questions with different options). A 5-item Likert's scale, from 1 to 5, was used.

We used ANOVA with pairwise comparisons for homogeneous samples and Welch's ANOVA with pairwise comparisons for non-homogeneous samples (Turkey's post-hoc test for equal variances and Games-Howel post-hoc test for unequal variances, Cohen's d) to analize the data.

{{margin-big}}

Key Findings

{{margin-small}}

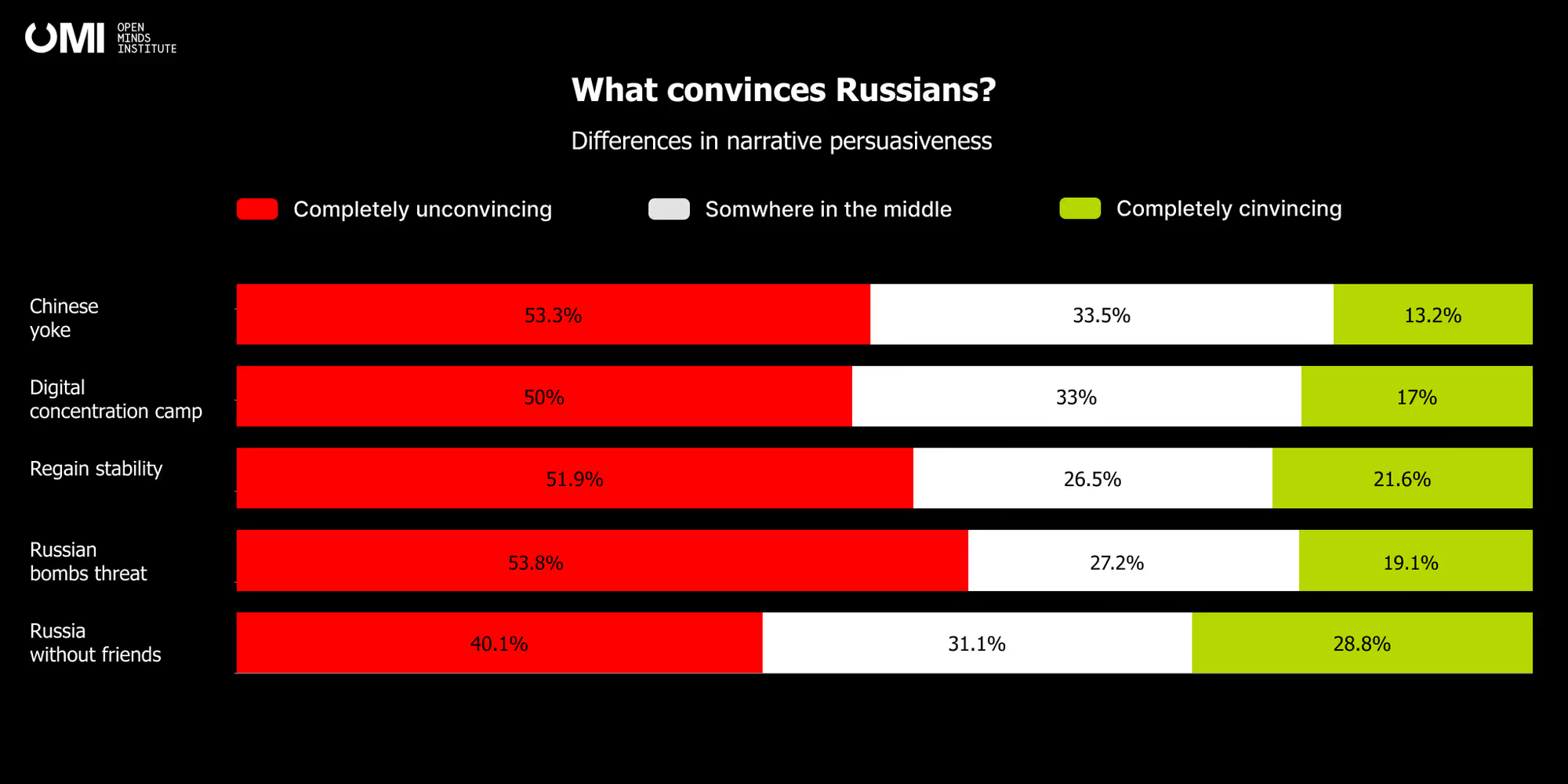

The results of the ANOVA revealed that all of the test narratives generated significantly lower levels of agreement from participants compared to the control narrative. The narratives that were found to be the most persuasive were those discussing Russia's declining number of allies and the importance of ending the war to regain stability. Interestingly, in the majority of the narratives, approximately one-third of respondents provided responses in the middle, indicating that these narratives may have the potential to be more persuasive to a significant portion of the Russian population.

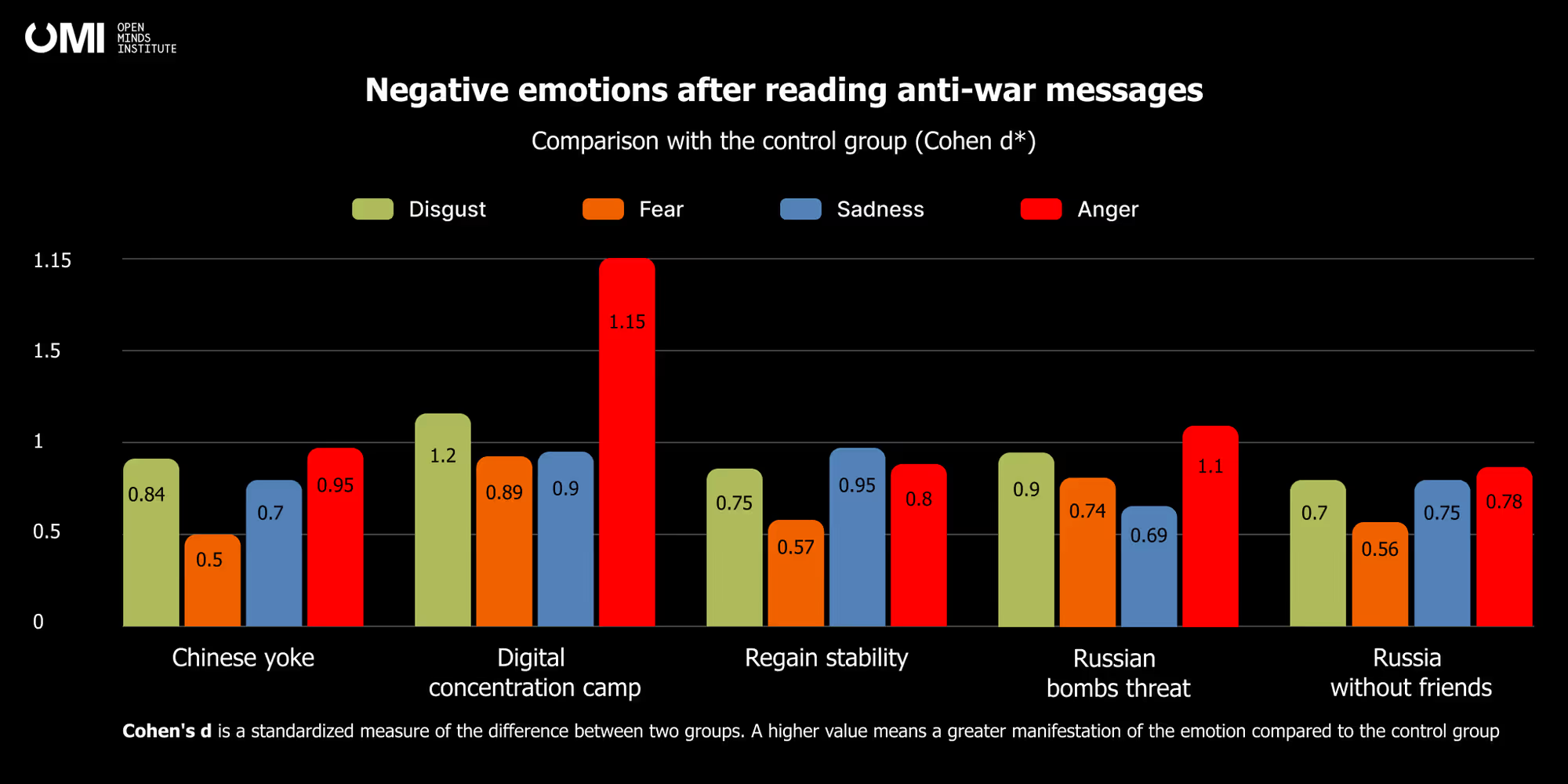

Respondents tend to experience negative emotions (anger, sadness, fear, disgust, etc., but not guilt) after reading the tested narratives compared to the control narrative. While narratives about Chinese control over Russia and the Russians were emotionally impactful, the strongest effect was observed in the narrative about the digital concentration camp, which tapped into concerns related to state surveillance and the use of QR codes during the COVID-19 pandemic. It elicited significantly more hatred, fear, and disgust compared to the control narrative. Reading about Putin's actions leading to instability, caused by military action against Ukraine, also generated strong negative emotions, including sadness.

The respondents demonstrated moderate surprise for all of the tested narratives, except for the narrative that Russia has no friends left. However, the statistical comparison between this narrative and the control narrative did not yield a significant result.

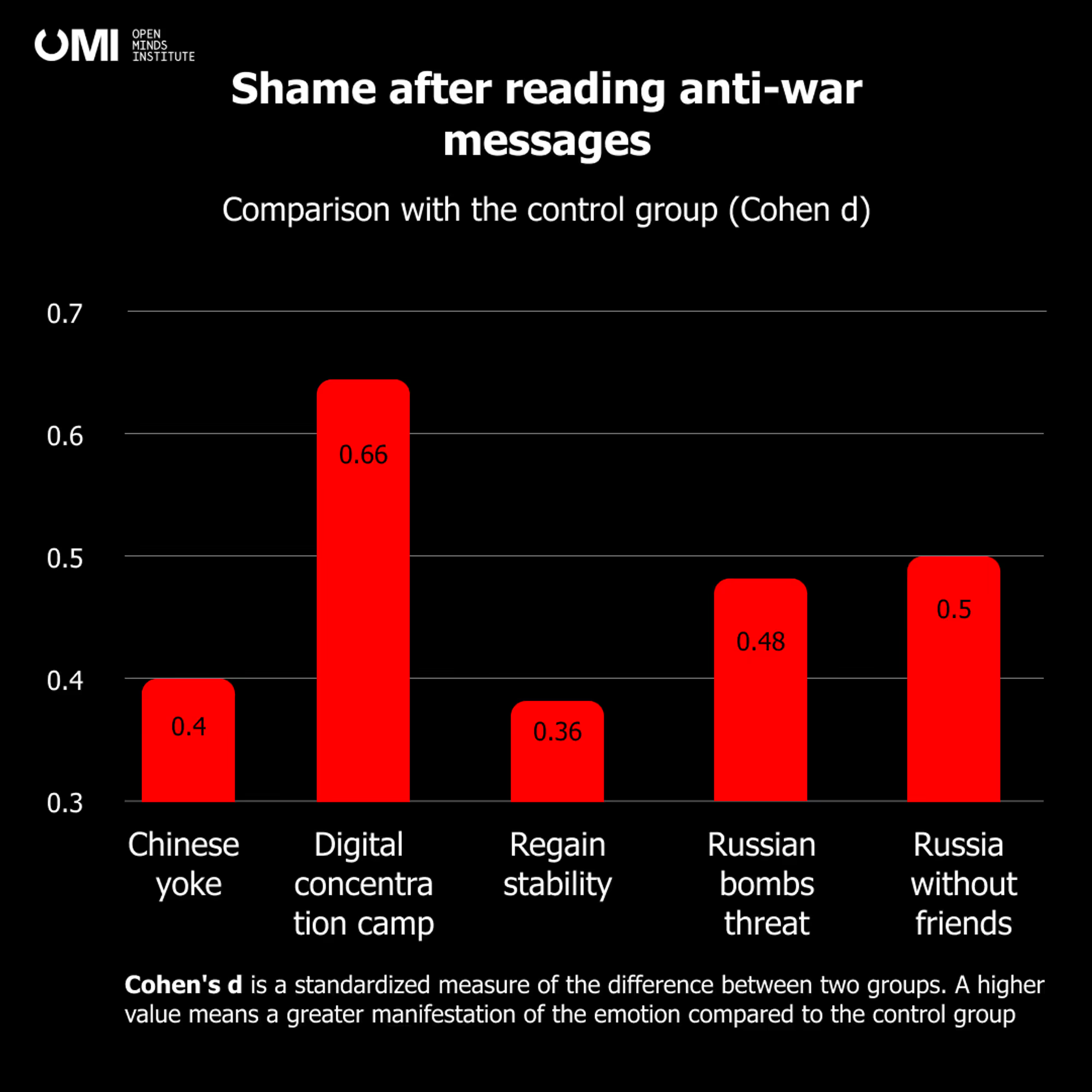

One surprising finding is that respondents experienced a significant level of shame when reading about the potential digital concentration camp that might be built in Russia with the help of China, as well as the Russian bombs that continue to be dropped on Russian cities due to obsolescence and oversight.

The study didn't reveal any noteworthy differences in attitudes between the respondents who read the experimental narratives and those who read the control narrative. This was evident in the responses related to the direction of the country, the correlation between Russian life issues and SMO, and the willingness to end the war with or without territorial concessions. One possible reason for this is that reading a single text may not have a substantial enough effect to alter attitudes toward the war.

{{margin-big}}

Conclusion

{{margin-small}}

The findings suggest that the tested anti-war narratives did not have a significant impact on the respondents' attitudes toward the war. However, the narratives did elicit strong negative emotions, particularly those related to the potential digital concentration camp and the threat of Russian bombs. These negative emotions could contribute to a sense of insecurity and distrust towards the Russian authorities.

The possible way to use the feeling of a malevolent totalitarian government in Russia to persuade Russians not to support the war would be to emphasize the connection between the war and the government's actions. By highlighting how the government's decisions have led to negative consequences for Russian citizens, such as the threat of Russian bombs, and by connecting these consequences to the government's broader authoritarian agenda, it may be possible to erode support for the war.

Additionally, by appealing to emotions like fear and disgust that are elicited by narratives about war, it may be possible to mobilize public opposition to the invasion. Ultimately, the use of negative emotions and narratives about an evil government must be approached with caution, as it may also lead to increased cynicism and disengagement among the public.

.svg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-01-2.avif)

-01.avif)

-01.avif)

-01%25202-p-500.avif)