Tradition & Obedience. What Makes Russians Support the War?

Introduction

{{margin-small}}

The OMI team decided to investigate whether Russians who believe their country needs a “macho” leader are more likely to support Putin and the war.

{{margin-big}}

Executive Summary

{{margin-small}}

- Obedience and identification with Russians are associated with support for the war and for Putin and, to an even greater extent, with support for Prigozhin and Kadyrov.

- Conservative morality and the idea of the moral degradation of society are negatively associated with support for Putin, Prigozhin, and, to a lesser extent, Kadyrov, the war in Ukraine, and mobilization.

- Belief in traditional masculinity and its importance is not positively associated with support for Putin.

- The very fact that a certain person has power is sufficient for his legitimacy: the root cause of his support is not the possession of strength but the presence of power itself.

{{margin-big}}

Sampling and Methodology

{{margin-small}}

The respondents were recruited online.

The final sample included 609 respondents, stratified by gender and age. The sample is also representative of the population of small and big cities in central Russia.

{{margin-small}}

As for the potential predictors of Russian leaders & war support, we have used the following:

{{margin-small}}

- Traditional masculinity: a belief that leader males should possess personality traits such as aggression, power, cruelty, and determination;

- National identification with Russians (whether a person identifies him/herself as Russian or a citizen of the world);

- Collective narcissism: a belief that one’s own group is exceptional but not sufficiently recognized by others.

{{margin-small}}

We have also used the questions from Altemeyer's Right-Wing Authoritarianism Scale, which was then divided into the following groups based on exploratory factor analysis:

{{margin-small}}

- Obedience: a belief that government is right, solely because it is the government and it has power;

- Conservative morality: belief that traditional values must be preserved to save the country and its leaders’ job is to confront the decline of morality;

- Strong leader: belief that the country needs a strong and tough leader;

- Ancestors respect: belief that respect for history and ancestors’ wisdom is key to the greatness of the country.

{{margin-big}}

Key Findings

{{margin-big}}

Leaders Preference

{{margin-small}}

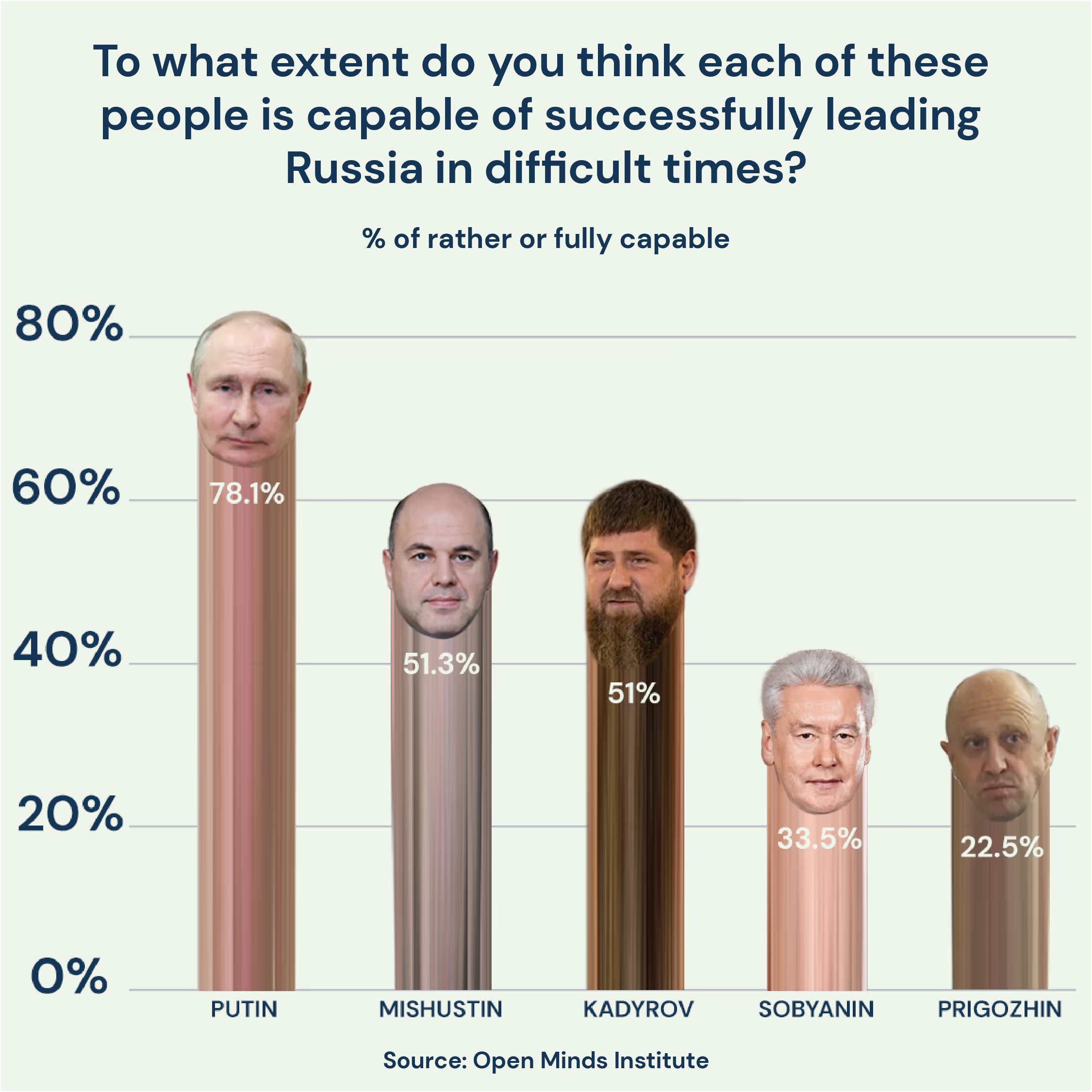

Respondents are confident that Vladimir Putin is the most suitable candidate for leading Russia during difficult and tough times. Following him, in descending order, are Mishustin, Kadyrov, Sobyanin, and Prigozhin.

{{margin-small}}

{{margin-small}}

These ratings for Putin and Mishustin fully mirror the satisfaction with their work conducted by FOM.

{{margin-big}}

Leaders Support Predictors

{{margin-small}}

Turns out, the strongest predictorі for Putin’s support as a leader in challenging times are national identification and obedience (β = .63 & β = .55, p < .001).

{{margin-small}}

.avif)

{{margin-small}}

That means that one of the key beliefs Putin supporters hold is that the government is always right because “it is the government.”

Conservative morality values have, on the other hand, a strong negative connection with his support: the more conservative people are, the less they support Putin (β = -.52, p < .001). It challenges the common perception of Putin as a conservative icon confronting the liberal cosmopolitan West.

The same predictors apply to Prigozhin’s and Kadyrov’s support, though collective narcissism also predicts support for the latter.

Belief in traditional masculinity and its importance for a leader turned out to be non-significant for the Russian government’s support.

{{margin-big}}

War Support Predictors

{{margin-small}}

Same as for the leaders above, the strongest predictors for war support are national identification with Russians and obedience (β = .36 & β = .19, p < .001).

Conservative morality is, again, negatively connected to war support (β = -.11, p < .05).

The mobilization support model presents an identical image.

{{margin-big}}

Conclusion

{{margin-small}}

As we can see, obedience and identification with Russians are associated with support for the war and for Putin and, to an even greater extent, with support for Prigozhin and Kadyrov. Obedience is a better predictor of support for these figures than collective narcissism and traditional masculinity.

Moreover, people with conservative morality are, contrary to popular discourse, less likely to support Putin and the war in general.

The current authorities are perceived by the respondents as “strong.” However, it seems that the mere fact that a certain person has power is sufficient for his legitimacy: the root cause of legitimacy is not the presence of certain characteristics but the presence of power.

This allows us to hope that if there is a change of power in Russia to a more moderate one, the attitude of Russians to the war will change significantly. The majority of Russians who support the war now will dutifully conform to the new government, just as they submit to the current one.

.svg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-01-2.avif)

-01.avif)

-01.avif)

-01%25202-p-500.avif)